Returning grazing land to nature helps more than wolves

It’s vital for wolves to have suitable habitat. Efforts are underway in the western United States to set aside grazing land for wolves and other animals.

By Tracy O’Connell

The importance of preserving wild-lands to provide healthy, spacious habitat for large carnivores and their prey has long been realized by environmentalists. The International Wolf Center mission, in support of that idea, is to advance the survival of wolf populations by teaching about wolves, their relationship to wildlands and the human role in their future.

One prominent cause of wild eco-system destruction is the grazing of domestic livestock such as sheep and cattle. Millions of acres of public land, managed by branches of the federal government such as the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), are divided into allotments and pastures for management purposes. There, the practice of domestic livestock grazing coexists with the wildlife native to the region.

The Forest Service, part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, notes on its website that it “supports livestock grazing on National Forest System lands.” Such grazing, the site says, “if responsibly done, provides a valuable resource to the livestock owners as well as the American people.”

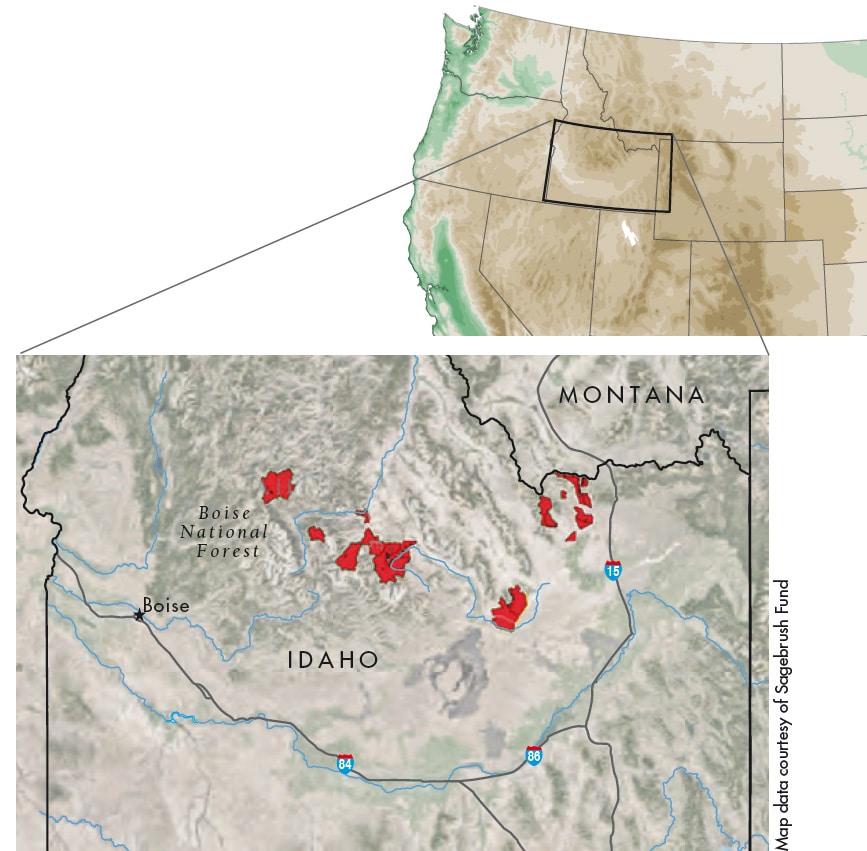

The highlighted area includes recently retired allotments in the headwaters of the East Fork of Idaho’s Salmon River, which will provide habitat for steelhead trout, bull trout and Chinook salmon, three top carnivores (wolves, bears and mountain lions), and bighorn sheep, among others.

In the U.S. Department of the Interior, the BLM’s Rangeland Administration System handles about 18,000 applications and issues 2,400 grazing authorizations (in the form of permits, leases, and other agreements) with ranchers each year across 12 western states, noting online that it manages the public lands for the use of both wildlife and livestock.

The sheer scope of the grazing allotment program, together with the myriad ecological concerns raised by grazing cattle and sheep on fragile mountain land, is why the retiring of grazing allotments—such as the more than 50,000 acres recently removed from the allotment program in the Upper East Fork of the Salmon River in Idaho—was a big deal to supporters of wildland preservation. One such supporter is Lynne Stone, director of the Ketchum, Idaho, based Boulder-White Clouds Boise Council, formed in 1989 to protect, defend and enhance Idaho’s wildlands and wildlife, according to its website. Stone notes that more than 39,000 acres of this retired allotment is in two new wilderness areas, the Jerry Peak and the adjacent Hemingway-Boulders, both created by Congress in 2015 and now protecting nearly 185,000 total acres.

This story was originally published in the Fall 2018 edition of International Wolf magazine, which is published quarterly by the International Wolf Center. The magazine is mailed exclusively to members of the Center.

To learn more about membership, click here.

Key to such an effort is the Western Watershed Project (WWP), whose executive director, wildlife biologist Erik Molvar, explained his group’s work. “It’s in the philosophical DNA of our organization to take on livestock grazing,” he says, adding that while frequently teaming with other conservation groups to achieve a goal, WWP is seen as a leader in the grazing issue—a topic many don’t want to touch because the grazing industry is very well connected politically. “We’re a hardnosed organization,” he says of WWP. “Regardless of the politics, we are free to take on problems and rock the boat.”

Molvar says his group, with offices in several western states, is armed with a multi-million dollar fund the WPP has dedicated to buying out allotments from willing sellers. That fund is managed by a “semi-separate” organization with a friendlier image—the Sagebrush Habitat Conservation Fund—that exists to negotiate with ranchers, some of whom might not meet willingly with WWP because of its perceived anti-grazing image. The group has worked to restore more than 250 million acres of public land in the west—places where an array of birds, fish, mammals, amphibians and rare plants flourish.

The monies used by the Sagebrush Habitat Conservation Fund resulted from a unique alliance between WWP and Ruby Pipeline LLC, a subsidiary of El Paso Corporation. Under a legal settlement, WWP agreed not to oppose a 680-mile underground pipeline project intended to bring natural gas produced in Wyoming and other Rocky Mountain states to Oregon for distribution to West Coast customers. In exchange, Ruby agreed to pay $15 million over 10 years to be used for voluntary conservation projects.

When the Conservation Fund purchases land to return it to wild habitat and protect it from grazing, “It’s a win-win,” according to Molvar. The sellers typically want someone to take over the land, often because their children choose to forego ranching, with its marginal income, in favor of other careers, he explained. “We give them a golden saddle to ride off into the sunset.”

While the return of grazing allotments to wildland provides much-needed space for large carnivores to live free of conflict with ranchers, it also brings multiple benefits to the rest of the ecosystem. Molvar ticks off examples of environ-mental degradation caused by grazing, and the improvements that occur as the livestock leave.

“Ranching takes all the natural forage away from the native herbivores,” he begins, noting that bighorn sheep, bison and elk can be driven from an area used for livestock grazing by lack of forage. Additional harm comes from the trampling of vulnerable soil biocrusts which contain microscopic communities that capture nitrogen from the air and hold moisture, among other functions. One hoof print can destroy these crusts for 30 to 100 years, he says.

By destroying native grasses through heavy grazing, cattle provide an open-ing to the invasive cheatgrass (so called because it sends out long roots to cheat other grass of water) to take over. “Livestock are rototilling the land and creating conditions for cheatgrass mono-culture,” Molvar explains. Also called drooping brome, cheatgrass is an annual plant native to the Eurasian steppes, and because it seeds much more prolifically, it can eliminate competing native perennials such as bunchgrass and sagebrush. Highly flammable when it dries out in the summer, it is blamed for some of the severe fires in western states.

Damage to waterways is another detrimental effect of grazing allotments. Molvar explains that cattle evolved in a boggy, northern European landscape and spend a lot of time wallowing in streams. In addition to breaking down stream banks and eroding soil, they cre-ate a “serious to extreme” risk of e coli from their droppings, which pollute wild streams with bacteria to an extent often in violation of the Clean Water Act. Among its other work, WWP seeks to ensure that land management agencies such as the BLM and the Forest Service enforce environmental laws, including the Clean Water, Endangered Species, and National Environmental Policy acts.

Domestic livestock can spread disease to wild populations, as well. In the case of cattle, brucellosis can be transmitted to bison and elk. Cattle ranchers some-times want bison killed to eradicate the threat of transmission to cattle, Molvar says, when it was actually the cattle that infected the wild herbivores.

Domestic sheep can spread the bacterium, Mannheimia haemolycta, which is harmless to them but can wipe out a bighorn population with a serious illness similar to pneumonia. Whole wild herds have been eliminated by this condition to which bighorn sheep develop no immunity.

“This region was an American Serengeti, as described by Lewis and Clark,” Molvar comments, adding, “No one alive today has ever seen the massive herds of wildlife that roamed the western range.” “People say wolves kill the prey,” he continues, but points to Yellowstone National Park as an example of one of the best places to see elk, which is also an excellent place to see wolves. Elk are abundant where domestic livestock are not competing with them, he says, noting that WPP looks to strategically create large tracts that, by being free of livestock, also provide an area for wolves and bears free of conflicts with ranchers.

While the areas removed from grazing are large, often the protections achieved are not permanent. “Most allotments are only closed for the life of the 20-year forest plan,” Molvar explains, after which they can be reopened. Of the half million acres WPP has restored from grazing, more than 400,000 acres are permanently closed to livestock. Other times the Forest Service changes its policies one way or another so land that was considered protected is re-opened to grazing. On still other occasions, the passage of time and the natural destruction of fences lead to de-facto permanent preservation because it becomes too problematic to restore the required fencing in order to reopen the allotment.

As the Sagebrush Habitat Conservation Fund project helps reduce live-stock grazing, create de facto permanent preservation, and allow retiring ranchers to benefit wildlands and wildlife, this does seem like a win-win.

Tracy O’Connell is professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin-River Falls in marketing communications and serves on the Center’s communications and magazine committees.

More articles of interest

The International Wolf Center uses science-based education to teach and inspire the world about wolves, their ecology, and the wolf-human relationship.