SCAT

Coyotes and wolves use a variety of tail positions to communicate with other members of their species. It can be very difficult to differentiate between wolves and coyotes by sight alone.

Test your knowledge! Join us every Friday for an exhilarating exploration of wolf facts and trivia on our Facebook and Instagram pages. Test your knowledge and uncover fascinating facts. The answers are posted here each week and are just a hover away—flip the card and reveal the answers.

Coyotes and wolves use a variety of tail positions to communicate with other members of their species. It can be very difficult to differentiate between wolves and coyotes by sight alone.

Placing captive-born wolf pups in wild dens can help increase genetic diversity in highly endangered wolf populations. Pups raised by wild parents tend to be more successful than adult wolves born into captivity and released later in life. This process has been used with red wolf populations in North Carolina and Mexican gray wolves in Arizona and New Mexico.

The International Wolf Center’s dedicated wolf care team takes round-the-clock shifts to ensure that someone is always monitoring our pups and addressing their needs. Sometimes, this even includes sleeping alongside pups outside or in their "den" area.

Having adult dogs around our wolf pups helps the pups to get used to interacting with a larger canine before they join our adult pack. It can also help pups to be calmer around humans and more trusting of our staff, as they can learn from a dog’s example.

Researchers have found that play can have many important functions for wolf pups. It may help develop their muscles and endurance, allow them to practice using their hunting instincts, and reinforce social bonds between pack members.

While wolves‘ skeletal growth is complete at about one year old, they don’t usually reach sexual and behavioral maturity until later. Wolves that are a year old are often referred to as "yearlings" or "juveniles".

Genetic research on gray wolves in North America indicates that some early Indigenous dogs bred with wolves between 1,598 and 7,248 years ago. This resulted in the black coat color phase in the gray wolf population today.

Food possession behavior is not automatically related to a wolf‘s social rank within the pack. More confident wolves may be more successful in defending their food from others, but it’s acceptable for any wolf to protect the food they’re eating. Sometimes, if the carcass is large enough, the entire pack will eat together at once.

Based on Isle Royale National Park observations, moose that choose not to run from wolves have a better chance of survival. This may be because running triggers a heightened predatory response in wolves, because weaker and more vulnerable animals are more likely to run, or due to another unknown factor, like the individual’s personality.

The type of food a wolf eats can change depending on the season! For example, in Alaska, salmon can make up about 10% of a wolf’s diet seasonally. Also, in Minnesota, wolves have been found to forage for blueberries in the summertime when berries are readily available and prey is more difficult to hunt.

Wolves may engage in a behavior called "surplus killing" where they kill more than they can eat at one time when prey is especially vulnerable, but this does not mean they kill for sport. If the carcasses are left alone, wolves will revisit the area for weeks afterwards to take advantage of leftover food.

Deer hunter success in Minnesota has decreased slightly in recent years (from 33.8% in 2021 to 32% in 2023) despite no significant change in the wolf population. Research indicates that severe winters have a larger impact on deer populations in northern Minnesota than predation from wolves. The number of deer hunters in Minnesota has also been decreasing steadily, leading to a smaller number of deer harvested. This does not mean that hunters are less successful.

The "pack leaders" are the dominant male and female, usually the parents of the other wolves in the pack. The dominant male and female will often share similar roles, including caring for pups, hunting, and defending territory. Males may tend to acquire food and defend territory, whereas females may focus more on direct care of pups and relationships within the pack. Pack relationships are also heavily influenced by the individual personalities of wolves.

Wolves may travel as a pack, in a smaller group, in pairs, or alone within their territory. They are more likely to travel individually or in small groups during spring and summer as they are usually foraging for food to bring back to the pups and dealing with smaller prey. In winter, they tend to travel as a pack because they usually hunt for larger prey, and traveling through the deeper snow is easier for a group. However, they may still spend some time alone.

The Red Wolf and the Gray Wolf are the only two universally recognized separate wolf species in the world today. With the use of molecular genetics, some researchers have concluded that there may be more separate species of wolf, but this requires more research to be widely accepted.

Wolf dispersal allows wolves to explore new territories and maintain genetic diversity. They can travel up to 550 miles, typically dispersing 50 to 100 miles from their birth pack. This behavior begins at 1 to 2 years of age, with 5 to 20 percent of the population dispersing at any time to find mates, establish territories, or join new packs.

Pup survival is directly related to prey availability. Prey availability is generally higher in areas being newly colonized by wolves, where wolves have been recently reintroduced, or where adult wolves are harvested.

Pup survival rates are primarily dependent on parenting of the dominant pair.

Wolves consume a variety of prey, primarily ungulates like deer and moose. However, they also eat beaver, berries, and occasionally fish. The availability of prey directly influences the wolves’ diet.

Wolves only eat ungulates.

Although wolves can sprint faster and can reach up to 38 miles per hour, typically, they will travel around 5 mph.

Wolves travel at an average speed of 5 mph.

Female wolves typically weigh between 60 and 80 lbs, and males are typically between 70 and 110 lbs. Average weights will vary greatly by region. Wolves also exhibit sexual dimorphism, meaning that males and females have physical differences. Females are usually slightly smaller

Dens are made from what is available in the territory. Most importantly, they are hidden and can fit the pups and members of the pack.

Dens can be in a hillside, under a tree, in a cave-like rock structure, or in a hollow fallen log, depending on the landscape and resources available.

This is an important adaptation for arctic wolves. Instead of their blood vessels restricting blood flow to their paws in the cold, blood flow increases to their paws. The increase in blood flow warms their paws and allows them to walk on the frozen landscape without paw injuries.

Arctic wolves often have paw injuries because of walking on the cold snow for most of the year.

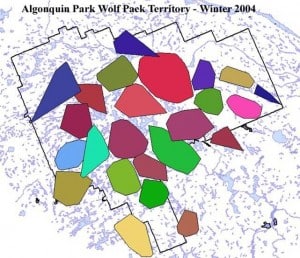

A territory is a pack‘s wild space to find resources like food, water, and shelter. The size of a pack’s territory can vary depending on prey density or how much food wolves can find in that area. The pack’s territory might be smaller in an area of high prey density (plenty of prey animals in a certain area). In areas of low prey density (like the Arctic, where prey animals such as musk ox spread out over a large expanse), wolves must travel farther to find their next meal; their territory might be much larger. Pack size can also have an influence on territory size as well. However, the main factor is prey density.

The size of a wolf pack’s territory is determined primarily by prey density.

Maintaining a territory gives wolf packs exclusive (of other packs) access to prey. However, maintaining it, in other words, defending it, can be costly. To balance the cost and benefits, wolves choose the smallest suitable territory possible with enough prey for the pack to survive.

Wolves choose the smallest suitable territory possible.

Wolf biologists monitor wolves using radio collars that connect to a special antenna, GPS collars that send data to a computer, camera traps, and traditional survey methods of tracking paw prints, kill sites, and scat. Tracking wolves can be challenging in the spring, summer, and fall when vegetation is dense and camouflages well in their environment. This is why wolf research has primarily been done in the winter; however, technological advancements have made it easier to track wolves year-round.

Wolf biologists use several methods to track wild wolves, such as GPS, radio telemetry, camera trapping, and traditional tracking (paw prints, scat, etc).

Although wolves are known as social carnivores, they do not hunt only as a pack. During dispersal, when a wolf is alone searching for a new territory, it will hunt alone. Additionally, during the spring and summer, wolves may go off in small groups or alone to hunt for smaller prey or to fish. while the other wolf or wolves in the pack watch the pups at the den or rendezvous site.

Wolves do swim! The webbed paws which help them walk on top of snow, are also helpful for swimming. Wolves can cool off in a water source when the weather is warmer. Some wolves even hunt fish and other aquatic or even marine animals. Click here to read more: https://canadiangeographic.ca/articles/the-amazing-sea-wolves-of-the-great-bear-rainforest/

A wolf pack will roam and defend a territory of between 25 and 100 miles in the western Great Lakes area. Territories can reach hundreds of square miles where prey densities are in low density such as in northwestern Canada.

Wolves are crepuscular, with higher activity at dawn and dusk. This often follows the patterns of their prey. Wolves are also opportunistic hunters and will take opportunities to hunt when possible. There are times throughout the day and night when wolves rest and times when they hunt. For more information on hunting and feeding behaviors, click here: https://wolf.org/wolf-info/basic-wolf-info/biology-and-behavior/hunting-feeding-behavior/

Wolves hunt only during the night.

Wolves are often labeled as “opportunistic carnivores,” hunting for prey based on opportunity, not a specific method. For example, wolves may prey upon healthy animals that are hindered by deep snow or domestic livestock that are confined or have lost their adaptations for defense.

Wolves howl for defensive and social purposes, not at the moon. They are crepuscular animals, usually more active at dawn or dusk. At night, when the moon is high, their howling is more audible due to the quieter human sounds. A howl can travel 6-7 miles, allowing us to hear them from a greater distance in the quiet of the night.

Wolves have a good sense of smell—about 100 times greater than humans. They use this sense for communication in a variety of ways. Wolves mark their territories with urine and scats, a behavior called scent–marking. When wolves outside the pack smell these scents, they know an area is already occupied. Pack members can likely recognize the identity of a packmate by its urine, which is useful when entering a new territory or when pack members become separated. Dominant animals may scent mark through urination every two minutes.

Howling is the one form of communication used by wolves that is intended for long distances. A defensive howl is used to keep the pack together and strangers away, to stand their ground and protect young pups who cannot yet travel from danger, and to protect kill sites. A social howl is used to locate one another, rally together, and possibly just for fun.

Wolf packs are families. The dominant pair is the parents of the other members of the pack. Once their offspring reach sexual maturity (around 2-3 years old) they usually will disperse. When a wolf disperses, it seeks a mate and new territory, where it starts a new pack and becomes the dominant pair with its mate.

The activity patterns of wolves vary across seasons, locations, and individuals. Researchers have found that wolf activity patterns can be influenced by temperatures, prey activity and availability, probability of encountering humans, and breeding season. Therefore, there is no single pattern of activity for all wolf populations. For example, a study in Alaska found that wolves were more active in the summer, while a study in Poland found that activity peaks were higher in the winter.

Wolf communication is primarily through the use of body language and vocalizations, including howling and marking with urine or scat. Pups learn to communicate through play and interactions with pack members.

Even once the pup’s eyes are open, they stay close to the den. At times, the pups may explore up to a mile around the den but typically stay closer. Another pack member will stay with the pups while the pack hunts. During this time, the pups will explore, and socialize through play.

Wolf pups are born blind and deaf, opening their eyes around days 11-15. During their first 12 days, pups are limited to vocalizing and slowly crawling. When their eyes finally open, their eyesight is not fully developed yet. It continues to develop over the next few weeks.

If you see a pup alone, you may not be able to see the whole picture. Wolves are neophobic, afraid of new things. Older pack members watching the pups may be off to the side, watching just out of view. The pups might be waiting for the pack to come back with food. Another possibility is the pups are exploring around the den, and although they appear to be alone, they are not. Either way, you may see the pups, but do not be concerned, they are likely perfectly fine and exploring their territory

After their first month of life, the pups’ can be left unattended for short periods of time. Sometimes, the older wolves in the pack will all leave; other times, one or two will stay behind with the pups. Although the pups are not usually left unattended for long, a wolf pup on its own is not typically cause for concern. They are often left behind or could be exploring just outside of the den, under the watch of another pack member. At about six months old, the pups will start joining the pack on hunts.

The pre-denning time prepares the den for the pup‘s arrival. During the first month of the pups’ lives, the dominant female will stay with them nearly all the time to nurse and protect the pups. In these first weeks, the pups are dependent on their mother as they are born deaf and blind in the den.

Dens are made from what is available in the territory. Most importantly, they are hidden and can fit the pups and members of the pack. For more information on dens, read this article about a group of researchers finding a den and pups.

Fact or Scat?

Fact or Scat?Dens can be in a hillside, under a tree, in a cave-like rock structure, or in a hollow fallen log, depending on the landscape and resources available.

A wolf pack is a cohesive family unit consisting of the adult parents and their offspring of the current year and perhaps the previous year and sometimes two years or more. Wolf parents used to be referred to as the alpha male and alpha female or the alpha pair. These terms have been replaced by “breeding male,” “breeding female,” and “breeding pair,” or simply “parents.” The adult parents are usually unrelated, and other unrelated wolves may sometimes join the pack.

Ungulates have pointed hooves which cause them to sink into the snow as they walk. This added challenge can cause issues in the winter when snow depth is high. As they sink into the snow, the ungulates are using more energy to move throughout the wildlands.

Although snow depth can be consistent in a geographical area, different species interact with the snow based on their need, sizes, and adaptations. For example, wolves have thicker coats and webbed paws making it easier for them to walk on the snow without sinking. Grouse will use the snow to insulate from the cold by temporarily burrowing. Other small mammals, like vols or shrews, will burrow into the snow for warmth and safety. Because of the different interactions with snow and the sizes of the animals, each species thrives at different snow depths.

Although you may be able to predict the general amount of snow an area will get in a season, the snow depth in that area can change from year to year and even month to month. Snow depth is the measure of how much snow is on the ground at that moment. This can be dependent on the location (side of a hill, forest, lake), the other weather conditions (temperature, wind), and the ecosystem and habitats in the area.

Most wolf communication occurs through scent marks and howling, so it’s no surprise that finding an unclaimed territory uses the same methods. Wolves are able to smell the scat and urine in an area to determine if that area has already been claimed by a pack, or is available. Howling is also used as a howl can be heard from 6 miles away on a clear night.

Wolves are social carnivores, meaning they work as a group to survive. This extends beyond hunting to the social life of the pack and raising the pups. The dominant male and female are typically the parents of the other wolves in the pack, meaning the pups have their parents and older siblings to watch, teach, and care for them.

Wolves typically disperse between 2 and 3 years old. In their first year, they are growing and learning, while in their yearling time (from their first birthday to their 2nd), the wolves are still not fully developed to adulthood. At 2 years old, wolves are considered mature, and able to disperse to find a mate and new territory.

Dispersal is a dangerous time for a wolf. Wolves are pack animals, and rely on that structure for much of their life. Searching for a new mate and an unclaimed territory can be extremely dangerous. Wolves may encounter other packs, roads, towns, or environmental factors that could threaten their survival.

The International Wolf Center uses science-based education to teach and inspire the world about wolves, their ecology, and the wolf-human relationship.