Gray wolves to be removed from Endangered Species Act protections

In September, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service told the Associated Press that, by the end of 2020, gray wolves would no longer be federally protected in the lower 48 states.

Given that, it came as no surprise that it was formally announced on Oct. 29 that wolves will be removed from the Endangered Species List. The final rule will be effective 60 days after publication in the Federal Register, meaning that the ruling would take effect on Jan. 4, 2021. Jurisdiction for wolf management will now return to each state, similar to management of deer, bears and most resident species. In the short term, this ruling mostly impacts Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota as wolves in those Great Lakes states are federally protected under the ESA. In the long term, this ruling means there will be no federal protections for gray wolves in any state.

Of course, legal challenges are expected to be filed in response to this delisting. In fact, the first challenges were filed Nov. 5, 2020. More information on those can be found here.

So what would it look like if wolves did not have those federal protections? Will there be hunting seasons on wolves across the lower 48 states? What’s next for wolves?

Those are important questions we hope to answer here as well as through regular updates on our website at wolf.org and through our various social media platforms.

Background

Gray wolves have had an on-again, off-again relationship with the Endangered Species Act since they were first listed as endangered by the Endangered Species Preservation Act in 1967 and legally protected in 1974 by the Endangered Species Act of 1973. There’s no question the Act helped wolf populations in the lower 48 states. Populations rebounded naturally in some places and with reintroduction efforts in Yellowstone National Park and Idaho.

The gray wolf population in Minnesota appeared to stabilize and that population helped grow the number of wolves in northern Wisconsin. That population then spread into Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. In the early 1980s, meanwhile, wolves that had dispersed from Canada were crossing over the border into northwest Montana. That population was bolstered by the Yellowstone reintroduction in 1995 and 1996.

As their numbers grew and met the biological criteria of the USFWS wolf recovery plans, efforts began to remove wolves from the Endangered Species Act. Congress delisted wolves in Montana, Idaho and parts of Utah, Washington and Oregon in 2011. In other parts of the country, such as the Midwest, wolves have been on and off the list and were federally protected until this recent decision by the USFWS. The estimated 10,000 wolves in Alaska are not and never were protected by the Endangered Species Act.

The latest ruling means that no states have federal protections in place for gray wolves, including those where wolves do not currently live. If wolves were to repopulate Utah, for example, they would not be federally protected. This doesn’t mean they won’t have any protections at all however. Wolves in California, for instance, are protected by state laws, having been granted protection by the state’s ESA in 2014.

Going forward, each state will determine the level of protection wolves receive and how they are managed.

Why did this happen?

In its original proposal to remove the wolf from federal protection, the USFWS wrote: “We propose this action because the best available scientific and commercial information indicates that the currently listed entities do not meet the definitions of a threatened species or endangered species under the Act due to recovery.”

State management plans in Wisconsin, Michigan and Minnesota have long included state-prescribed minimum populations. Those minimum population figures were surpassed, according to state estimates, many years ago.

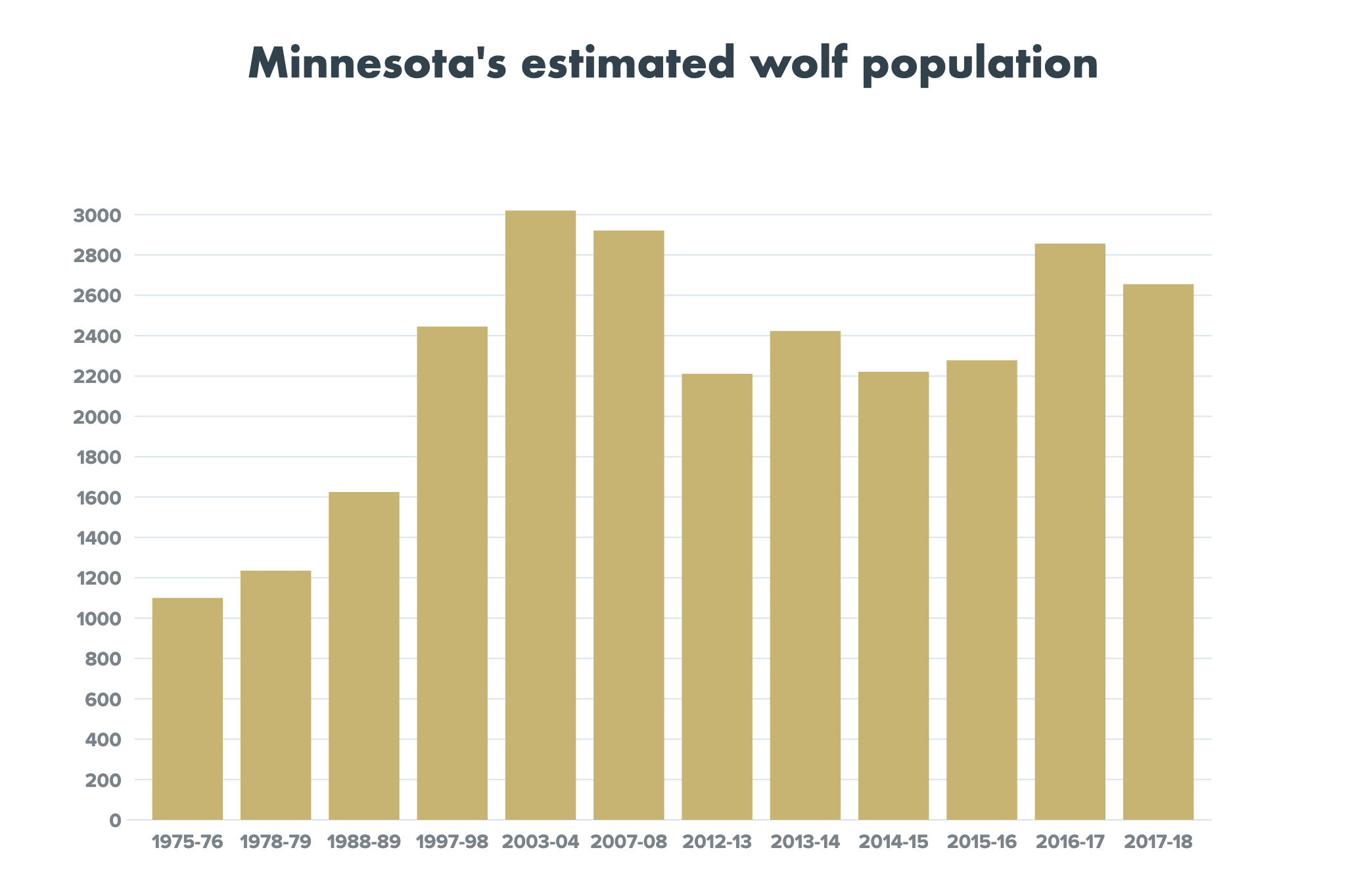

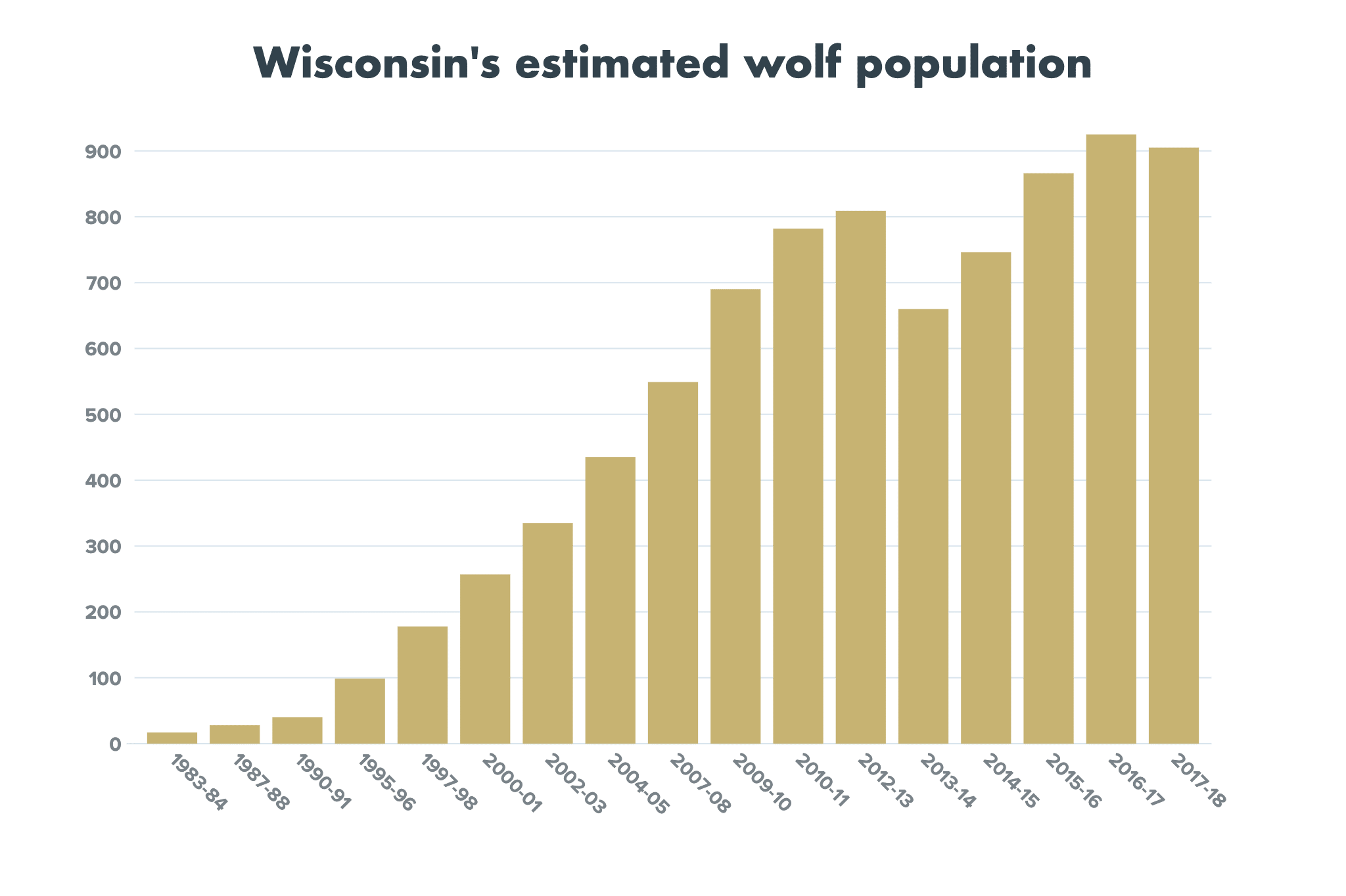

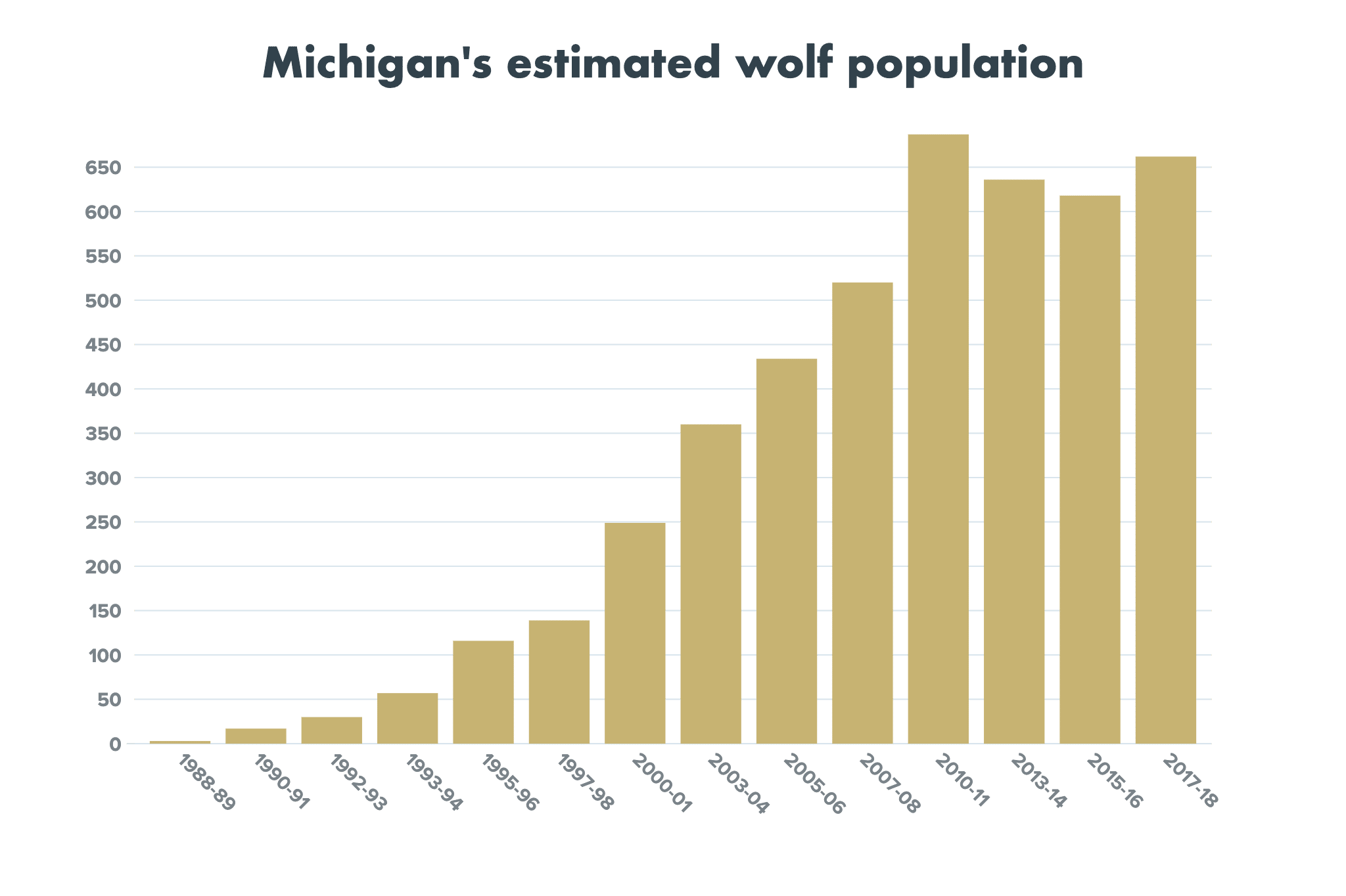

In Minnesota, for example, the minimum population of 1,600 was reached many years ago. The Wisconsin target of 350 and the Michigan target of 200 have also been eclipsed.

Minnesota hosts an estimated 2,600 wolves. Wisconsin estimates a minimum of 1,000 and Michigan nearly 700. The USFWS wolf recovery plan only required at least 100 wolves between Michigan and Wisconsin combined, and 1,250 in Minnesota for at least five consecutive years.

Estimates, though, are just that. Many wolf supporters think the population estimates are overcounting wolves. Wolf detractors, meanwhile, believe that the wolf populations are underestimated. (To watch a webinar on how the MN wolf population is estimated, follow this link: bit.ly/mnwolfcount).

What was the process for delisting?

The USFWS says that the ultimate goal of the Endangered Species Act is to “recover species so they no longer need [federal] protection. Recovery plans describe the steps needed to restore a species to ecological health.”

Wolf Recovery Plans were written by biologists with federal, state, local agencies and tribes.

The Department of the Interior issued a press release about the ruling, which reads, in part:

“The United States Fish and Wildlife Service based its final determination solely on the best scientific and commercial data available, a thorough analysis of threats and how they have been alleviated and the ongoing commitment and proven track record of states and tribes to continue managing for healthy wolf populations once delisted. This analysis includes the latest information about the wolf’s current and historical distribution in the contiguous United States.

“‘After more than 45 years as a listed species, the gray wolf has exceeded all conservation goals for recovery,’ said Interior Secretary David Bernhardt. ‘Today’s announcement simply reflects the determination that this species is neither a threatened nor endangered species based on the specific factors Congress has laid out in the law.'”

To read the full press release, click here.

To learn more about the ESA process, click here.

What happens next?

States with wolves have management plans for them, and some states are updating them.

In Minnesota, for example, a group of residents representing farmers, trappers, hunters, environmentalists and the general public have been meeting to discuss significant updates to the state’s plan, which was last updated in 2001.

The last time these three states managed their own wolf populations was 2012, 2013 and 2014, when the wolf was delisted for a few years. During that time, regulated public wolf hunts were held in Minnesota (2012-14), Wisconsin (2012-14) and Michigan (2013 only).

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service will monitor wolf populations for five years to “ensure the continued success of the species,” according to the press release they issued on Oct. 29.

Want to learn more?

To see the proposed rule to remove the gray wolf from the Endangered Species Act, follow this link.

To read more about the work being done to update Minnesota’s wolf management plan, follow this link. This work will be especially important as Minnesota has the largest population of gray wolves in the lower 48 states.

To learn more about the history of the gray wolf’s status on the Endangered Species Act, click here.

To view a detailed timeline on the history of the gray wolf in the contiguous United States, click here.

Mexican wolves

This ruling does not pertain to Mexican wolves or red wolves.