Memories of Wolves from the Superior National Forest Wolf-Deer Study

Stories told by L. David Mech | Stories written by Cree Bradley

Stories told by L. David Mech | Stories written by Cree Bradley

Over fifty years of wolf data were collected through Minnesota’s Superior National Forest (SNF) Wolf-Deer Study. This achievement built a wealth of understanding about wolf-prey relationships, population dynamics and scent-marking as it developed and refined methodology adapted and used by researchers around the world.

Nearly equal in measure to this scientific legacy, for Dr. L. David Mech – or Dave – who initiated the study, are the enduring memories garnered from 1966-2022 through his experiences with the wolves themselves. Some wolves taught Dave valuable lessons about how to trap, how to improve trapping, and whether ever to trap again. Other wolves possessed a curiosity or some behavior that was intriguing or entertaining to behold. And yet another, Wolf 2407, captivated Dave’s imagination and earned his gratitude for all that her life contributed to the study.

Just as the data were gathered, so too, were the stories – endearing memories of specific wolves, as told by Dave himself:

Dave Catches His First Wolf

Near the start of the SNF study in 1968, Dave hired trapper Bob Himes to provide expertise in catching wolves to be radio-collared. The first wolf Bob and Dave caught, using Bob’s trapping leadership, was Wolf 1051, captured along the Powwow Lake Road. They then caught Wolf 1053, Wolf 1055, and more. But it was soon after Wolf 1051 was caught that Dave, having trapped mink, bears and other wildlife, decided to try his own hand at wolf trapping near the Ogishke Muncie Lakes in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW).

It was January then – a good time to catch wolves, but not a good time to trap them, due to the risk of a trapped foot freezing. This was a learned lesson, not something realized early in this first trapping season. Soon thereafter, Dave limited winter trapping.

Bob had been setting traps along roadsides, but to catch his first wolf, Dave decided to innovate , based on what he knew of wolf behavior and the fact that he was trapping in roadless lake country. He took a trap with him on a radio-tracking plane, thinking that if they found a trail of fresh wolf tracks on a lake, Dave would have the pilot put him down to set a trap along the trail. Sometimes wolves re-use their own tracks, and Dave hoped he’d see some repeat use in the area, enabling him to capture a wolf.

After finding a line of tracks, Dave set up a trap along the track-trail, marking it with a little spruce tree. He put the tree through the chain of the trap and stuck it into the snow so he could easily see the tree, and thus the trap, from the air. In addition to being a marker for the trap placement, Dave was also using the tree as a potential lure for the wolves. To wolves, walking on the lake nearby, but not along the same track-trail, the tree itself might draw the curious creatures to check it out, which would bring them near the trap.

Dave and the pilot flew day after day, looking at the spruce tree. If it was present, the trap would be intact, and there was no wolf captured. If the tree was gone, they would know that a wolf had been captured and had dragged the trap someplace nearby, with the tree in tow. But for days, the tree stood in its original place.

Then, a few days later, it turned out that Dave’s intuition had worked! He captured and located his first wolf – part of a big pack that had crossed the lake. After that early success, Dave decided to trust his own skills and instincts and began trapping wolves and becoming less reliant on professional trappers. He still used trappers such as Himes to run two different trap lines, allowing him to increase wolf captures and more quickly initiate the study.

This first wolf Dave trapped was one of hundreds captured over more than 50 years . Yet this first wolf-catch was one of the most thrilling experiences for Dave. As a life-long fur trapper, capturing his very first wolf was a memory not soon, if ever, to fade.

Wolf 1051 Heads Far West

As mentioned above, Wolf 1051 was the first wolf that Bob Himes and Dave caught and radio tagged. That was in November 1968 on a road north of Isabella Lake at a time when the road was not gated, and one could drive farther into the BWCAW than today.

A large Hollywood crew from MGM was visiting the area to film a documentary on wolves, so the fact that Bob and Dave had captured and tagged their first wolf was a big deal. The project had truly commenced now that they had their first wolf to study, and the Hollywood crew was excited about it, too.

Tracking Wolf 1051, they quickly learned that this wolf spent a lot of time wandering all over that widespread area north of Isabella Lake and in the adjacent BWCAW. But toward the spring of 1969, Wolf 1051 did what many wolves do – it dispersed from the area and moved west.

Dave was aerially radio tracking the wolf about once a week. One day, he picked up its signal many miles west, by Highway 53 somewhere between Cotton and Canyon. When Dave found the wolf, he watched it come out of the woods, head down an embankment toward the highway, and interestingly, stand there looking up and down the road before he crossed. When there were no cars coming, it ambled across the road, repeating the watchful behavior in the median of the 4-lane divided highway before making its final crossing and ambling into the woods where it chased a deer and disappeared.

Dave never did see the deer kill on the west side of Highway 53, though he believes it’s likely that Wolf 1051 did get the deer. Nor did he ever see the wolf again. Ultimately, he lost the radio signal further southwest, about 60 miles away near Big Sandy Lake. But just watching Wolf 1051, the project’s first-ever captured and collared wolf, travel so far out of the study area – a good 50 to 60 miles southwest of the BWCAW – was thrilling. It was a bit sad, as well, to watch it amble across the highway and beyond, departing the area for good.

Collaring a Conscious Wolf

That first fall and winter of radio tracking was still early in the learning process: when to trap, when not to trap, what kind of sets to make and how to handle the wolves they caught.

Wolf 1059 was about the fifth one caught along the Spruce Road south of Ely, and Dave decided to try handling this wolf without injecting drugs. He had previously used drugs to anesthetize the wolves for handling. It had worked very well and would remain his dominant handling system going forward. But with Wolf 1059, since there was yet a lot to learn about handling, Dave decided to try a drugless approach that he had learned from a biologist from Ontario, who had caught a few wolves to collar without using drugs. Instead, he pinned its neck to the ground with a forked stick, put a muzzle and a blindfold on it, and tied it up so that it could be handled safely.

Dave had a professor from Macalester College and at least four students working with him at the time. Dave told the professor how they were going to handle this wolf and asked him to find or cut a branch to make a forked stick. Soon after, Dave heard a heavy “chop-chop-chop,” and thought, “What the heck is he cutting?” Dave had thought that a hunting knife would do the trick.

As it turns out, even though the professor had seen the wolf and knew its size, he must have had an inflated view of what was needed to handle a non-drugged wolf. The professor had chopped down an aspen tree a few inches thick, when all Dave needed was a stick an inch-or-so wide. The professor delivered that beast of a forked pole, and Dave found it impossible to use, for the fork was so big it would have straddled the entire wolf – not pinned the neck.

Finally, Dave showed the crew what kind of stick was needed, and a student brought over a much smaller one. They pinned the wolf by the neck, blindfolded and muzzled it, tied up its feet, and it all worked remarkably well. Dave was surprised to see that the wolf went into a trance-like, calm state. They were able to put the ear tags in, collar it and measure it before turning it loose.

Or at least they tried to turn it loose. They untied its feet and took the blindfold off. Then they took the muzzle off. The wolf was free to leave. But instead of running or even walking off, the wolf just lay there. And it lay there. And it continued to lie there.

Dave had everybody back away while he gently prodded it with a stick, but the wolf wouldn’t move. It appeared to be breathing just fine; it was blinking and looking around, but it wouldn’t move. All the crew could do was wait, as they weren’t about to leave it without knowing it was able to resume its natural wolf life. After 90 minutes had passed, Wolf 1059 finally got up and ambled off, struggling through the snowpack, but otherwise seeming fine. As Dave remarked, “It was the darndest thing.”

This was the only time Dave opted to handle wolves without the use of drugs. Though the experience generally went well, and the wolf seemed okay in the end, it was hard to fully understand what was behind the trance-like state and delayed departure. All things considered, Dave thought it was probably less stressful on the wolf for it to be unconscious while they conducted what can be intrusive procedures – especially since a year or so later, he began to collect blood samples, which may have been hard to do with a conscious wolf.

A Wolf on His Lap

Aerially radio tracking wolves about a day a week, Dave once found a wolf in the same place for two flights in a row, adding up to just over a week. He suspected something was wrong, for wolves usually move around much more than that.

Dave and his crew decided to check on that wolf, hiking into the site northeast of the Tomahawk Trail. Sure enough, the wolf had been caught in someone’s fox trap. Traps must be checked daily, but this wolf had been left in the trap far too long. The animal was in poor shape and needed to be rescued if it were to live.

Dave and his crew took the wolf back to their headquarters at Kawishiwi Lab, where they put it in a large cage and gave it food they purchased from the Ely grocery store – fat and bones, dog food and meat – anything that would get its weight back to normal.

After about a week, the wolf seemed to be in pretty good shape. Its weight was up, and its health had returned. It was time to release the wolf, and Dave figured if he released it near where it had been caught, the wolf would recognize the place and resume its life more easily.

It was winter, and conditions had degraded. The decision was made to fly the wolf back to the catch site in a very small Super Cub aircraft – just a two-seater, pilot in front and one person in the back.

Dave lightly anesthetized the wolf; he didn’t want to leave a deeply sedated wolf out in winter conditions. He tied its mouth and feet to handle it more safely, and held it on his lap as a passenger in flight. Dave, the pilot, and the wolf flew out to the Isabella Lake area.

As they flew, Dave could tell the wolf was doing okay. It was alert, eyes open and blinking. It began to move around slightly, but that didn’t concern Dave. The wolf was stable, and he preferred some movement over sedating the wolf more deeply.

Eventually, while still alert, the wolf propped its head against the window, and to Dave, it appeared as if the wolf was looking out over the water and woods of the SNF and the BWCAW directly over Quadga Lake, and taking it all in, just as a human might do. Despite how scientifically objective and non-anthropomorphizing he usually is, Dave couldn’t help but ponder in that moment, “What is this wolf thinking? Is he looking down onto Quadga Lake and thinking, ‘Oh, there’s Quadga Lake! Yah, that’s a pretty nice lake down there!’”

The pilot, the wolf, and Dave eventually landed. Dave untied the wolf and dropped it off in the woods. He waited for the wolf to fully awaken from its shallow sedation and watched it walk off, healthy and back in its territory, where it remained with what was probably a unique, once-in-a-lifetime memory for a wolf – an aerial view of Quadga Lake and the rest of its territory. Asked how he felt about the experience, Dave stated, “It was super!”

Trapped Wolf Swims River

When Dave and volunteer helper Dr. Bob Brander started to live trap wolves along the Kawishiwi River, they were still naïve about wolf trapping and made the mistake of setting traps along a deer trail that ran along the bank, parallel to the river.

One day they discovered a trap was missing. These types of traps were not staked to a tree or other solid object. They had instead an 8-foot chain with a metal drag on the end of it. The idea was that when a wolf was caught, it would run off, and eventually the drag would get caught up in the brush or on a log, stopping the wolf in place, where it could be tracked down by the marks the drag left in the plant undergrowth and the ground.

With the trap missing, Dave and Bob were pretty sure they had a wolf and started to follow the drag marks—which went right down the bank and into the river. Feelings of hope and dread crept into them when they knew the wolf had gone into the river. They hoped the wolf had crossed the Kawishiwi and made it safely to the other side. But dread reminded them it was possible the wolf had drowned.

They got back into their canoe and crossed the river, delighted to find that the drag mark had come out of the river on the other side. It was there, on the far side of the Kawishiwi River, that they found their wolf, alive and well, and did what they had set out to do—collar and collect data on the wolf, and release it back into the wild.

Dave learned a very valuable lesson from that experience. You never trap near open water of any sort, because the wolf might run into the water and drown. At the time, he had an enduring thought: “Oh my gosh, why were we so dumb?!” Fortunately, this wolf swam 50 to 60 meters across the Kawishiwi River with 5 to 10 pounds of chain and drag attached, and Dave was very grateful that it made it.

Famous Wolf 2407

Wolf 2407 was a female wolf, at least one-and-a-half years old when caught for the first time on October 10, 1971. She had a den in the Harris and Heart Lakes area of the SNF, just north of theTomahawk Trail, and she occupied an area of at least 30 square miles with her Harris Lake Pack packmates over the years.

There were several small roads and grades that dotted her territory, and those allowed Dave and his crew to set traps. By chance, they ended up catching her a second time, which is fairly unusual. It’s always good to get a recapture on a wolf, because the collars in those early days lasted only about one year. A second capture allows a collar change and a longer history to be gathered on the same wolf, which is extremely valuable.

Wolf 2407 was recaptured a third time, and then a fourth, and was recollared each time. By this point, Dave realized how truly significant this wolf was because of the many years of data gathered. This one animal, with four years of data, and counting, was technically more valuable than any of the wolves with only one or two years of data gathered.

Dave began trying to recapture her again and again, which became harder and harder as she became savvier to the traps. He felt fortunate when he captured her for the eighth time, but that didn’t happen without significant innovation and considerable trap nights expended.

For example, Dave attempted to rig up some special trap sets designed to outwit Wolf 2407. One such set utilized a water puddle next to the road – nothing large enough to risk drowning her, but enough to hide a trap. He placed the trap in the puddle and laid a piece of sod on the pan of the trap, so it made a steppingstone of sorts through the puddle. Beyond that, he would bait or add a scent lure to attract her. Brilliant! Or so he thought. But this rigged trap failed to catch 2407. In fact, she would pull the trap out of the water, leaving it wolf-less along the road in the puddle’s wake. (One can’t help but question whether mockery was at play, or if that’s just the nature of wolves.)

By the eighth and final capture, it was very difficult to outwit Wolf 2407. She was extremely trap shy, which is why it took so long to recapture her that final time. Dave spent a total of 8,000 trap nights trying to catch her – 5,000 one summer without luck and another 3,000 the next summer, finally with success. (A trap night is one trap out for one night, so 10 trap nights may be 10 traps out for one night, or one night out for 10 traps).

Dave caught Wolf 2407 for the final time on August 28, 1982 by making a creative set he had never made before. He dug a hole next to the road, only 3 to 4 inches wide, but quite deep. In the hole, he inserted the end of a deer leg, so that only the end of the pointed hoof was sticking out above the hole. Wolf 2407 took an interest in the hoof, which was just behind the trap – and that was the trap that captured 2407 for the final time.

After that eighth capture, Dave and his crew never learned the fate of Wolf 2407. After about four months, they lost her signal, which meant she may have dispersed or that her transmitter failed. Eventually, of course, she would have died or been killed.

As noted in Dave’s essay, “Minnesota Wolf 2407: A Research Pioneer,” in the book “Wild Wolves We Have Known,” Wolf 2407 was located more than 1,300 times during her life and was observed with her packmates nearly 500 times. She was a pioneer for wolf research, contributing considerable information about movements, territoriality, mate tenure, longevity, reproduction and many other aspects of wolf ecology and behavior. She provided important experience for many of the young wildlife techs who worked for Dave and continued their careers in wolf research and conservation.

Finally, Wolf 2407 was an inspiration to Dave himself. Though her final whereabouts, her pack structure and the last days of her life were lost to Dave, her enduring and endearing legacy remains firmly rooted in his memories as one of the most special wolves he had the pleasure to interact with and learn from.

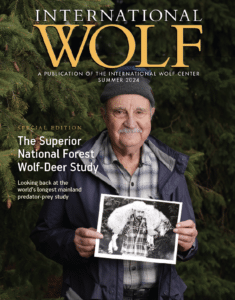

This story was originally published in the Summer 2024 edition of International Wolf magazine, published quarterly by the International Wolf Center. The magazine is mailed exclusively to members of the Center.

Cree Bradley is a member of the International Wolf Center board of directors and, with her husband Jason, owner-operator of the nearby Chelsea Morning Farm and Never Summer Sugarbush. Through her off-farm work in Minnesota public lands and the Superior National Forest, she encounters many wildlife.

To learn more about membership, click here.

The International Wolf Center uses science-based education to teach and inspire the world about wolves, their ecology, and the wolf-human relationship.