Learn about wolves and depredation

Wherever they coexist, wolves may prey on domestic animals. However, wolves normally prefer natural prey such as deer and elk. When wolves kill domestic animals it is called depredation.

Wolves and domestic animals have interacted since the domestication of livestock in areas such as Europe, Asia and the Middle East, and in North America since the arrival of Europeans with dogs and cattle. Yet efforts to understand and manage wolf and domestic animal interactions in the United States without whole-scale eradication did not begin in earnest until the mid 1970s.

Minnesota – as an example

Wolves became completely protected in Minnesota in 1974 under the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA). The responsibility to deal with wolf-caused livestock and pet losses then fell to the federal government. In 1975, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) began trapping at farms experiencing verified* wolf depredation. Wolves that were captured from 1975 to 1978 were translocated (moved) because they were listed as endangered under the ESA, and could not be killed. In April 1978, wolves in Minnesota were downlisted from endangered to threatened. This new classification allowed the USFWS (and since 1986, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)) to destroy wolves that kill livestock.

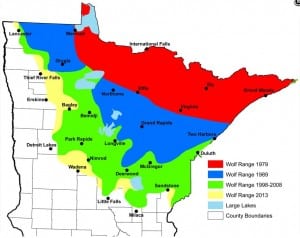

Since their protection, wolf numbers in Minnesota have steadily increased. Federal management gave way to state management in January 2012. The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources estimated the wolf population in Minnesota at approximately 2,200 (with a variation of 500+/-individuals) animals during the winter of 2012-13.

As the wolf population has increased, their range has ceased to expand significantly southward and westward. The gray wolf’s range in Minnesota is now approximately 43,496 square miles (70,579 square kilometers). Even with the population increasing, verified wolf depredation claims are somewhat stable with a five year average of 70 verified complaints annually.

Even during times of high numbers of depredations, only a small portion of Minnesota farmers are affected. In 2013, a total of 65 farms out of 74,400 farms had livestock depredations and another 5 had dogs killed. These livestock-raisers are eligible for compensation of fair market value per animal by the Minnesota Department of Agriculture. Producers are not compensated for losses to other predators, such as bear or coyote. Compensation payments paid to Minnesota farmers in 2011 added up to $102,230, down from $106,615 in 2010.

The number of wolf depredations may actually be higher than reported, as many claims of wolf depredation, such as missing calves, can not be verified. Even though this is true, the view of wolves as livestock predators has sometimes been exaggerated, as depredation caused by coyotes, dogs, and bears is often misidentified by farmers as wolf depredation.

Most verified losses occur from May through October when livestock are released to graze in open and wooded pastures. Some animal husbandry practices, such as calving in forested or brushy pastures and disposing of livestock carcasses in or near pastures, have been believed to contribute to wolf depredation in Minnesota. However, research(3) has indicated that these factors do not contribute to wolf depredation.

Cattle, sheep, and turkeys are the domestic animals most often taken by wolves, however, domestic dog depredation does occur. Wolf depredation on dogs has become more common in recent years as wolves have colonized areas with higher human densities. Dog owners in wolf territories can reduce the opportunity for wolves to depredate by keeping pets inside or in an enclosed kennel when wolves are know to be in the area.

Verified wolf depredation on domestic animals in Wisconsin and Michigan (dogs are not compensated in MI) are compensated at 100% of the estimated value of the livestock.

Northern Rocky Mountains

In the western U.S., gray wolves began to naturally recolonize northwestern Montana in the early 1980s. The first den was discovered in 1986 in Glacier National Park. Wolf numbers increased in Montana to a peak of around 90 animals in 1996, but a severe winter in 1996/1997 reduced the wolf population to 60-70 individuals. Nearly all the packs in northwestern Montana had livestock, primarily cattle, in their territory and routinely encountered domestic animals. Since 1987, when the first depredation on livestock occurred, the USDA Wildlife Services and the USFWS cooperatively documented and resolved conflicts between wolves and livestock. In accordance with the Service’s wolf control plan, problem wolves were usually moved after the first offense, but if they depredated again they were killed. Wolf control affected less than 6% of the wolf population in northwestern Montana annually. Agencies also tried aversive conditioning, radio-collaring and releasing wolves on site, and placing problem wolves in captivity. Translocating problem wolves and immediately releasing them has been largely unsuccessful at preventing further livestock losses and at keeping wolves alive in any region.

Wolf damage is often significant to individual ranchers, however, and is always emotional. Fortunately, the Defenders of Wildlife initiated a private livestock compensation program that has reimbursed all producers who had confirmed wolf-caused losses. Their program paid out $1,368,043 to livestock producers in Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming from 1987-2009 when the program came to an end.

Wolves were reintroduced from Canada to central Idaho and Yellowstone National Park in January 1995 and 1996. Wolves adapted to their new home better than expected and by late 1999 there were around 120-150 wolves in each reintroduction area and there are now approximately 1,500-2,000 in a combined population including the naturally occurring population in northwestern Montana and new populations in Washington and Oregon.

Before wolves were reintroduced, the Service predicted that 100 wolves would kill about 10 – 20 cattle and 60 – 70 sheep annually in each of the two areas (Yellowstone NP and central Idaho). Verified losses have actually been much lower, averaging 4 cattle, 18 sheep, and 1 dog in central Idaho and 7 cattle, 25 sheep and 1 dog in the area around Yellowstone. In response to these depredations, as of 2012, 96 wolves had been moved and 896 had been killed in Montana; 20 wolves had been moved and 598 had been killed in Idaho, 1 wolves have been moved and 411 have been killed in Wyoming. Under federal protection, wolves observed attacking livestock could be legally shot by livestock producers under the experimental – nonessential rule.

Wolf restoration efforts in the northern Rocky Mountains has been successful far beyond predictions. As a result, wolves are part of the western ecosystem and are being enjoyed by the public. Hundreds of thousands of visitors to Yellowstone National Park alone have had the opportunity to hear and observe wolves. With success comes the responsibility to protect local residents from an unreasonable level of livestock losses caused by wolves. The Defenders program certainly made a difference but depredation control is still necessary, especially now that wolves in this region are state managed. Wildlife managers must occasionally kill wolves that depredate on livestock so that this behavior does not become common in the general wolf population. The bitter debate over wolf restoration is largely over . Wolves have returned to the West and they are here to stay. In the future the debate will increasingly have to focus on the use of lethal methods to control wolf-caused problems, unless some new non-lethal method is found. So far, millions of dollars have been spent seeking such a method for coyote depredation control, but to little avail.

*A verified complaint is one in which USDA officials determine that wolves have killed or maimed one or more domestic animals as evidenced by (1) observing wounded animals or remains of animals killed and (2) finding evidence of wolf involvement.

Original article authored in 2000 by Bill Paul, U.S. Department of Agriculture – Wildlife Services, Ed Bangs, retired Wolf Recovery Coordinator, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services, Carter Niemeyer, U.S. Department of Agriculture – Wildlife Services, Elizabeth Harper, Fisheries and Wildlife Department, University of MN

Updates by International Wolf Center staff

Literature cited

1. Fritts, S.H., W.J. Paul, L.D. Mech, and D.P. Scott. 1992. Trends and Management of Wolf-Livestock Conflicts in Minnesota. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Resources Publication 181. 27pp.

2. Paul, W.J. 2000. Annual update of Minnesota wolf depredation statistics. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Grand Rapids, Minnesota. Unpublished report.

3. Mech, L.D.., E.K. Harper, T.J. Meier, and W.J. Paul. 2000. Assessing factors that may predispose Minnesota farms to wolf depredations on cattle. Wildlife Society Bulletin 28(3):623-629. Jamestown, ND: Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center Online.

4. Bangs, E.E., J.A. Fontaine, M.D. Jimenez, B. Cox, T.J. Meier, and D. Boyd. Gray wolf restoration in the northwestern United State. Proc. of Beyond 2000: Realities of Global Wolf Restoration. 23-26 February 2000, Duluth, Minnesota.

5. Bangs, E.E., S.H. Fritts, D.R. Harms, J.A. Fontaine, M.D.Jimeniz, W.G. Brewster, and C.C. Niemeyer Control of Endangered Gray Wolves in Montana. Pages 127-134 in L.N. Carbyn, S.H. Fritts and D.R. Seip Eds. Ecology and Conservation of Wolves in a Changing World. Canadian Circumpolar Inst. Occa. Publ. No. 25, Univ. of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada.

6. Bangs, E.E., and S.H. Fritts 1996. Reintroducing the Gray Wolf to Central Idaho and Yellowstone National Park. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 24(3):402-413.

7. Bangs, E.E., S.H. Fritts, J.A. Fontaine, D.W. Smith, K.M. Murphy, C.M. Mack, and C.C. Niemeyer. 1998 Status of gray wolf restoration in Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 26:785-798.

8. Paul, W.J. 2003. Annual update of Minnesota wolf depredation statistics. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Grand Rapids, Minnesota. Unpublished report.

Updated January 2014