Into a wolf den

In northern Minnesota, scientists track the next generation of wolves

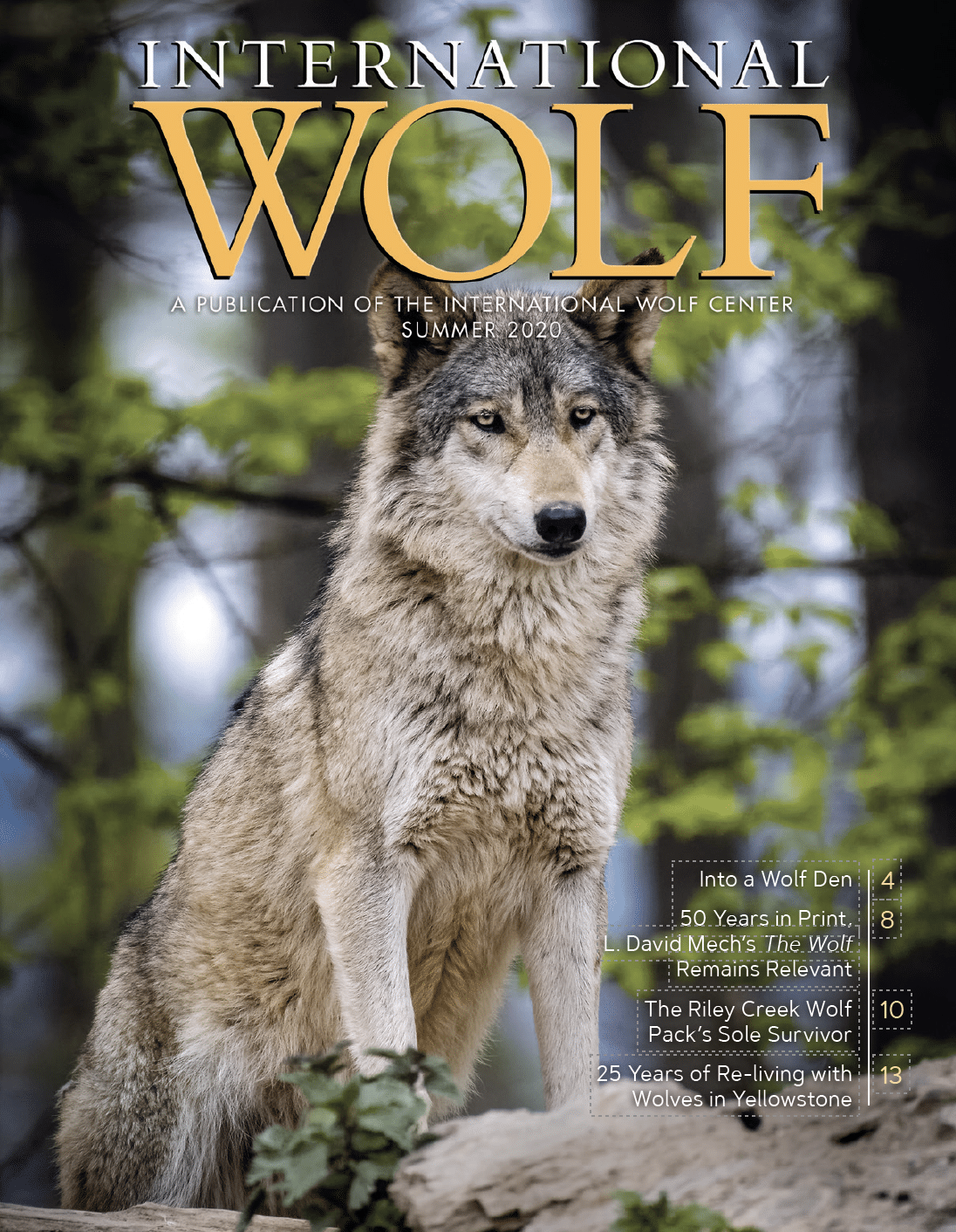

Editor’s note: This story was first published in the summer 2020 issue of International Wolf magazine.

By Cheryl Lyn Dybas

First stop on a scientific research expedition that starts before dawn: the White Earth National Forest west of Bemidji, Minnesota. On this chilly, early May morning, patches of snow still dot the woods.

As part of a pilot project to monitor wolf pup survival in northern Minnesota, state Department of Natural Resources (DNR) biologists Carolin Humpal and Barry Sampson, along Shannon McNamara, wolf biologist, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, set out in four-wheel-drive trucks to find a wolf den hidden in a dense forest of red pine and white spruce.

Reaching the edge of the White Earth forest, the researchers turn off the highway and into unmarked territory. Bumping along in their trucks, they pick their way down an old, overgrown logging road where sections have been washed out by the high water of spring snowmelt.

Shannon McNamara carefully carries a wolf pup out of a well-hidden den in a leaf-covered hillside.

Photo by Ilya Raskin

This story was originally published in the Summer 2020 edition of International Wolf magazine, which is published quarterly by the International Wolf Center. The magazine is mailed exclusively to members of the Center.

To learn more about membership, click here.

The scientists head toward a female wolf on which they had placed a GPS collar over the winter. The past month’s data show that she has settled in one place—a clue that she’s denned under a tree or in a hillside and likely has pups.

“After we see that signal,” says Humpal, “we wait about four weeks, then come out to the spot. Usually by then the pups are old enough to be taken out of the den briefly so we can see how many there are and whether they’re healthy, then immediately place them back inside.”

Stopping by wolf woods

Like mariners of old looking for “X marks treasure” on a map, the biologists locate the general area where the den might be. Then they unload sup-plies and carry them down a trail that’s slippery from recent rains.

The researchers peer at the bases of trees, look under logs, and check vegetation-covered hillsides for signs of wolf presence and a den.

Sampson spots recent wolf tracks near a slope choked with tangled brambles. “The mother wolf is prob-ably around somewhere,” he says, “but she’s unlikely to show up while we’re here. She can smell our scent and may see us—although we probably won’t get a glimpse of her.”

Suddenly Humpal says, “I think I see the den.” Spotting a place where the vegetation looks trampled and dirt is strewn around what appears to be an opening, she straps on her head-lamp for a better look. “Yep, that’s it.”

Even what looks like a sure bet for a den, however, often presents challenges. With the voice of experience, Sampson says the spot may instead be a resting place. A den may be too small or the surrounding soil too unstable, making it dangerous to enter. Pups may be too small to collar. The list seems endless.

Success: Seven Pups

The researchers remain hopeful, how-ever. They set up their pup exam area on the grassy top of a knoll just above the den and quietly make their way to the opening. Head-lamp firmly in place, Humpal carefully shimmies into the narrow, dark space until only her boot-clad feet are visible.

In less than a minute, Sampson pulls her out. She’s carrying the first of seven pups that appear to be four or five weeks old. “They were all snuggled up in there,” says Humpal. “That’s how we usually find them.” The pups are part of the Bad Medicine wolf pack, named for nearby Bad Medicine Lake.

From birth to 14 days old, wolf pups have dark fur, rounded heads and are unable to regulate their body temperature, according to educators at the International Wolf Center in Ely, Minnesota. Closed eyes and tiny ears render them blind and deaf, and a pug nose provides little sense of smell, but their senses of taste and touch are nonetheless in working order. Movement is a slow crawl. They’re limited to sucking and licking, and will feed four or five times a day. Females gain an average 2.6 pounds and males 3.3 pounds each week for their first 14 weeks.

At 15 to about 24 days old, their eyes are open but their eyesight isn’t fully developed; pups can’t discern forms until weeks later. Milk incisors are present at 15 days, when pups can eat small pieces of regurgitated meat from their parents. At this age, they begin to stand, walk and make some vocalizations, including whimpering and squeaks, as well as their first high-pitched attempts at howling. “The four-week-old age is when pups start venturing outside and socializing,” says Sampson, who recently retired from the Minnesota DNR but, like a parent wolf to a den, came right back under part-time contract. Pups from 20 to 77 days old, scientists have found, begin appearing outside the den and playing near the entrance. At 27 days, their ears begin to rise and their hearing significantly improves. Around 31 days, their ears are erect but the tips still flop over. Canine teeth and premolars become visible.

Humpal continues her forays into the den. Once all seven pups are out and carefully placed together in a soft felt bag that rests atop the knoll, they curl up in one large ball. The researchers pull them out one at a time. They weigh every new member of the Bad Medicine pack—three females, four males—and give each one a unique piece of ear jewelry: a numbered tag that marks the date and location of the den. The biologists then record each pup’s sex, neck circumference, tooth eruptions and stage of development, and snag a piece of hair for DNA studies before placing a small, expandable breakaway VHF radio collar on its neck.

“Not all pups are well behaved,” says Sampson. “Sometimes they just chew off their collars.”

Filling in the gaps

To date, 57 percent of the pups have been males weighing an aver-age of 4.59 pounds, and 43 percent have been females weighing an average of 4.25 pounds, according to project leader John Erb, a wildlife biologist at the Minnesota DNR.

“Keeping track of wolf birth rates helps us develop better population models,” Erb says.

In a 2016 paper published in the journal PLOS One, Erb, along with International Wolf Center founder Dave Mech of the University of Minnesota and Shannon Barber, both with the U.S. Geological Survey Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, state that information about female wolf breeding in the wild is sparse.

“Although some basics are known about reproduction in female gray wolves, little or no information exists about the mean age of first reproduction, generation time, and the proportion of females that breed in wild populations in any given year,” write the biologists.

What scientists do know is that a wolf mother and her pups usually hang around a den until early summer. “Then ‘mom’ abandons the den and moves the pups to a rendezvous site,” says Sampson. Weaning is complete, and the pups feed solely on solid food.

The pups’ eyes begin to change from blue to yellow-gold. Soon they start following adults on hunting trips for short periods and return to the rendezvous site by themselves. They now weigh 22 to 30 pounds. What are they eating to fuel the growth spurt? Deer fawns and moose calves are born in late winter to early spring, offering adult wolves meals for their pups. As ice melts in lakes and ponds, beavers are also on the menu.

Beavers may be important food for pups, according to Robert Myslajek of the University of Warsaw and his col-leagues in Poland. The biologists published a paper in 2019 in the journal Ethology Ecology & Evolution document-ing the importance of beavers to wolf pups, titled “The best snacks for kids: the importance of beavers (Castor fiber) in the diet of wolf (Canis lupus) pups in northwestern Poland.”

Beavers are likely much more than wolf snacks, however. “Studies in wolf populations in North America and Eastern Europe have suggested that one of the most important supplementary food items adults deliver to pups is beavers,” the researchers write. In north-western Poland, “the share of beavers in the pups’ diet was higher than that in adult wolves, which could be evidence of selective provisioning.” Lower water levels in summer facilitate access to beavers, the scientists believe.

In a look at interactions between gray wolves and beavers published in 2018 in Mammal Review, Thomas Gable of the University of Minnesota and his co-authors found that “high beaver abundance can increase wolf pup survival, and beavers may subsidize wolves during periods of reduced ungulate abundance.”

How many Minnesota wolves?

If all goes well, pups grow up and become adult wolves. By the most recent estimate, Minnesota’s wolf population was 2,655 wolves in 465 packs—numbers derived from counts in the winter of 2017-18. The number is statistically unchanged from that of the previous winter.

The population survey is conducted in mid-winter, near the low point of the annual population cycle, says Erb. Following the birth of pups in spring, the wolf population usually doubles, although not for long; many pups don’t survive until the following winter.

“The accuracy of our wolf population estimate depends on radio-collaring a representative sample of wolf packs,” Erb says. Annual wolf capture efforts are focused on areas believed to represent the state’s overall wolf range, especially regarding land cover and deer density, according to Erb.

Minnesotans disagree about how many wolves in the state are too few and how many are too many. Barry Babcock, a resident of Laporte, Minnesota, writes in the Grand Rapids Herald Review that

“Minnesota is a special place where wolves and deer and people can coexist.” Babcock is a deer hunter, but says he’s lived with wolves “24/7/365 days a year. To a number of us deer hunters, it is more important to see a wolf than a deer.” It reflects a forest ecosystem in balance, he says.

The seven new members of the Bad Medicine Pack are good medicine for the White Earth National Forest and beyond, many believe. X indeed marks treasure, especially when the treasure chest contains little brown balls of fur hidden beneath a tree in Minnesota’s northern forest.

Ecologist and science journalist Cheryl Lyn Dybas, a Fellow of the International League of Conservation Writers, also writes for National Wildlife, Ocean Geographic, BioScience, Canadian Geographic, Lake Superior Magazine and many other publications.

The International Wolf Center uses science-based education to teach and inspire the world about wolves, their ecology, and the wolf-human relationship.