Hungry as a Wolf: What Wolves Eat

by Debra Mitts-Smith

This article was originally published in the spring 2022 issue of International Wolf magazine.

by Debra Mitts-Smith

This article was originally published in the spring 2022 issue of International Wolf magazine.

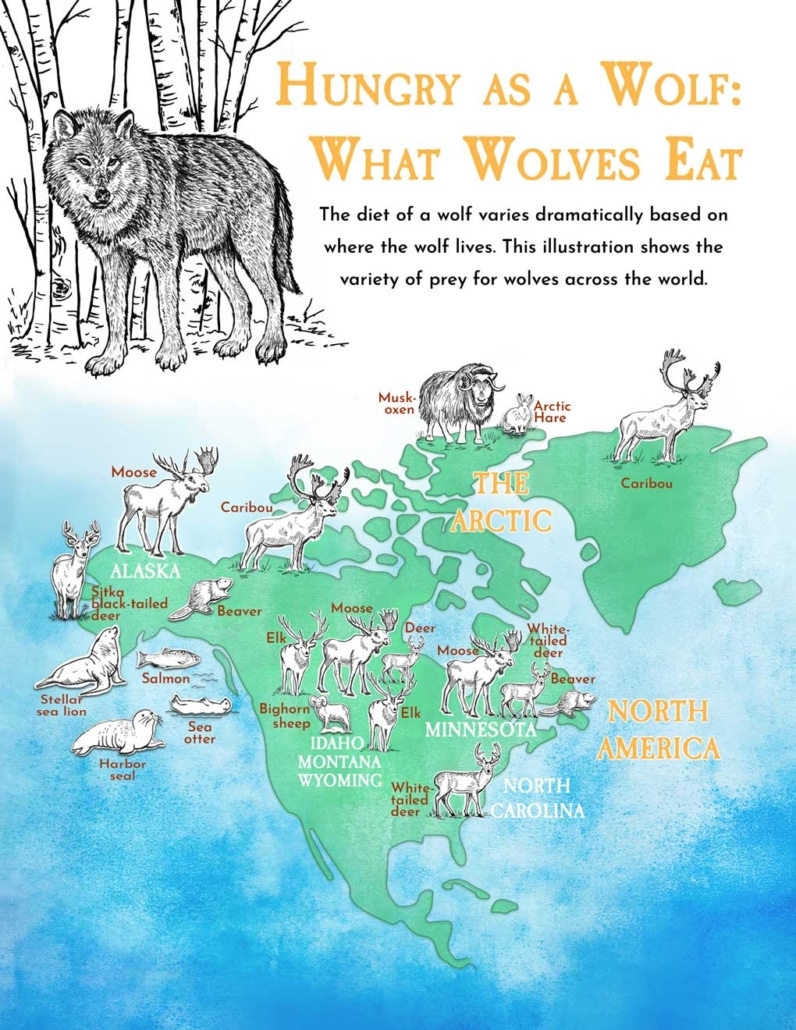

The wolf is a large carnivore whose main prey are large, hooved herbivores such as the moose, elk and deer that scientists call ungulates. Unlike several species of cat, which eat only meat (hypercarnivores), wolves have adapted to eating a more varied diet; they are generalists and opportunistic hunters.

The wolf is a large carnivore whose main prey are large, hooved herbivores such as the moose, elk and deer that scientists call ungulates. Unlike several species of cat, which eat only meat (hypercarnivores), wolves have adapted to eating a more varied diet; they are generalists and opportunistic hunters.

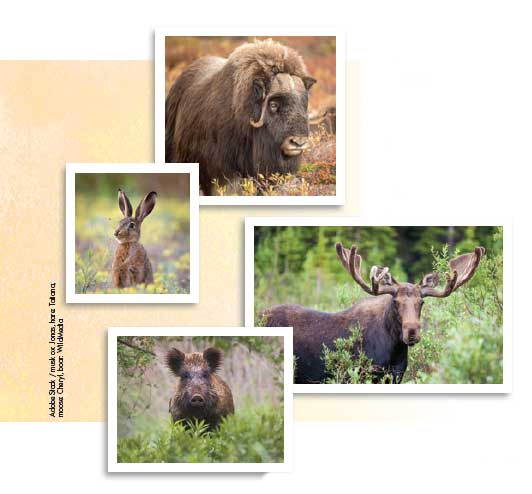

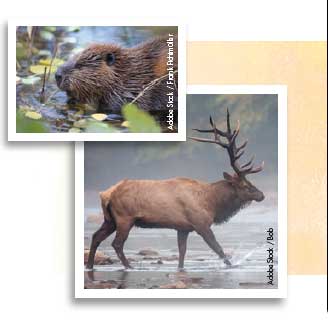

While ungulates are wolves’ primary prey, over half a century of research on wolves reveals that they also prey on smaller animals such as beavers, hares, marmots and rodents, along with fish and even birds. Wolves scavenge, too, eating carrion and garbage. They also prey occasionally on domestic livestock and pets—a conflict with some people that has earned wolves a bad reputation.

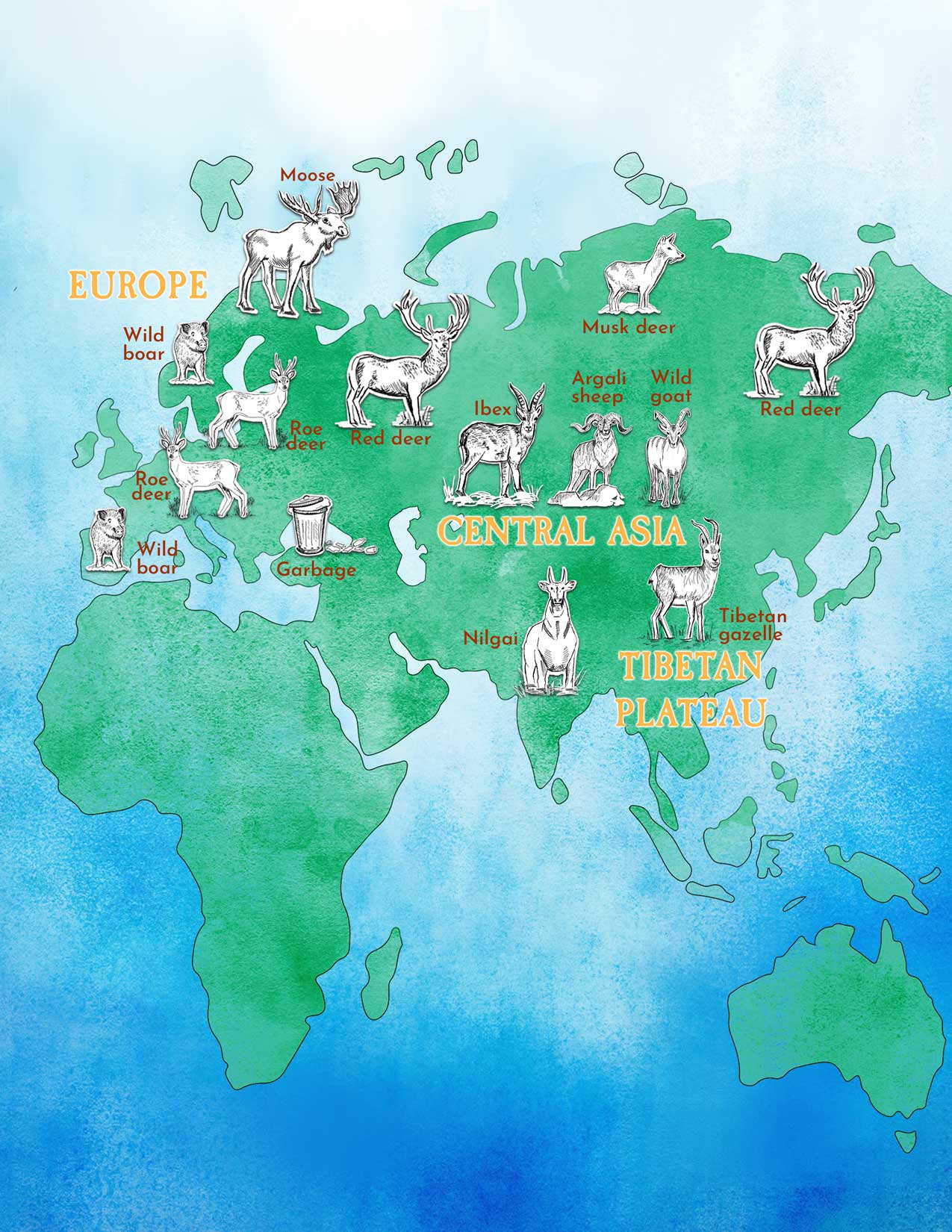

Wildlife biologists and paleontologists credit the wolf’s flexible diet, in part, for its success as a species, allowing it to survive and thrive in a range of ecosystems across the Northern Hemisphere, from grasslands to the vast, dry Arctic tundra. What wolves eat depends on the type of prey available, its size and its vulnerability. Wild ungulate species vary in kind and abundance across the Northern Hemisphere. Arctic wolves hunt caribou and musk-oxen while elk, moose, deer, bighorn sheep and mountain goats dominate the menu for wolf packs in Idaho, Montana and Wyoming. The Mexican gray wolf’s favored wild prey are elk and deer. In North Carolina, the red wolf hunts white-tailed deer. In parts of Spain and Italy, wolves tend to feast on red deer, roe deer and wild boar. In parts of Central Asia, the ibex, argali sheep and wild goats are the main prey of wolves. The Himalayan wolf—the oldest extant lineage of wolves—lives in the high altitudes of the Himalayan and Tibetan plateau, hunting Tibetan gazelles.

Wolves can survive on 2.5 to 3.7 pounds of meat daily, but they require 5 to 7 pounds per day for successful reproduction. Yet wolves typically do not eat every day. Instead, they live a feast-or-famine lifestyle. They can go days or even weeks without eating—and after successfully hunting a large ungulate, a wolf can consume up to 20 pounds of food in a single meal.

Although records exist of single wolves killing every prey animal, hunting large ungulates such as elk, moose, caribou and musk-oxen is much easier and safer for wolves that hunt in packs. Hunting and killing a large ungulate takes skill, energy and luck, and though wolves are skilled hunters, they are not always successful. Many factors affect the outcome of a hunt, including the age and experience of the wolf, the age, sex, vulnerability and experience of the prey, the time of year, time of day, the terrain and the weather.

Some of the most important wolf research has looked not only at wolves’ hunting strategies and behaviors, but also at the prey animals most susceptible to predation. These studies show that wolves tend to target the most vulnerable individuals in a herd or flock of prey species: the old, injured, sick or young, as well as prey with less visibly discernable vulnerabilities such as a history of poor nutrition.

The flexibility and resiliency of wolves becomes especially apparent where ungulates and other wild prey are scarce or absent from the landscape.

Studies have also explored whether the number of prey animals limit the number of wolves. For over half a century, Isle Royale has been the focus of the longest running predator-prey study on wolves. From 1959 to 1980, the moose and wolf populations of Isle Royale tended to reflect each other. When the moose numbers were high, there was more food for the wolves, meaning better nutrition, higher pup survival rates and an increase in the wolf population. More wolves eventually led to a decline in moose and less food for wolves, meaning fewer wolves survived. As wolf numbers declined, they put less pressure on the moose populations, which in turn helped moose numbers rebound, and the cycle repeats. Yet, even in an isolated ecosystem like Isle Royale, other factors such as deadly viruses, ticks and inbreeding can lead to a species’ decline.

In areas where more than one prey species is available, wolf-prey relations are even more complex. In multi-prey ecosystems, when the primary prey species goes into decline, two things can happen: the predator population may also go into decline, or the predator population may continue to increase by supplementing its diet with alternate prey. Biologists call this “prey switching.”

In the east-central Superior National Forest in northeastern Minnesota, white-tailed deer, moose and beavers are the top menu items for wolves. From 2006 to 2016, the moose population declined by more than half. To determine if wolf numbers also declined, or whether wolves supplemented their diet with an alternate prey, Shannon Barber-Meyer and Dr. L. David Mech compared wolf numbers before and after the moose decline. Their study, which tracked and counted radio-collared wolves, showed that as the moose population declined, the wolf population, instead of decreasing, almost doubled. Wolf scat revealed that wolves supplemented their diets by hunting white-tailed deer. They also continued to prey on moose calves, contributing to the continuing decline of the moose population. Only when the white-tailed deer population declined did the wolf population also begin to decline.

A recent study focused on what the wolves of the Alexander Archipelago and the southeastern mainland of Alaska eat when ungulates became scarce or absent. From 2012 to 2018, researchers from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game and Oregon State University collected 860 wolf scats from twelve study sites. DNA analysis of the wolf scat identified 55 food sources in the wolves’ diet. Although the study confirmed that ungulates represented roughly 65% of the wolves’ diet on a regional level, it also revealed that the kind and proportion of ungulates in their diets varied from one location to another. For instance, on the mainland, wolves’ main prey were moose and mountain goats, while on several of the islands, Sitka black-tailed deer were the main prey. As in other studies, when one of these ungulates went into decline or became scarce, wolves changed the prey that they hunted or scavenged. Surprisingly, the wolves in this study did not switch to just one or two alternate prey species as reported elsewhere, but instead expanded their dietary niche to include a variety of species that included land mammals (beaver, black bear, rodents and others), marine life (mammals and fish) and even birds.

In several other locations ungulates were not the main items on the wolf’s menu. For instance, the wolves who inhabit the area near Gustavus, on the shores of mainland Alaska, had the most varied diet. Here, moose comprised only 28% of the wolves’ diet, while sea mammals (mostly sea otters) comprised 22%. Black bears represented another 11% of their food while seasonally salmon made up 10% of their diet. The researchers suggest that the wolves opt for these other species because they are less dangerous and easier to hunt than moose. The mild coastal climate also makes possible year-round predating and scavenging of marine mammals on the shores near Gustavus.

Southeast of Gustavus, in the Icy Straits, lies Pleasant Island where both Sitka black-tail deer and moose are found. Wolves arrived on Pleasant Island in 2013, and moose and deer numbers went into decline. Yet, despite the scarcity of these ungulates, wolves remained on the island. Scat analysis revealed that moose and deer made up only 13% of the wolves’ diet. While the predators did hunt or scavenge sea otters, Stellar sea lions and harbor seals became the predominate food source for wolves.

Southeast of Gustavus, in the Icy Straits, lies Pleasant Island where both Sitka black-tail deer and moose are found. Wolves arrived on Pleasant Island in 2013, and moose and deer numbers went into decline. Yet, despite the scarcity of these ungulates, wolves remained on the island. Scat analysis revealed that moose and deer made up only 13% of the wolves’ diet. While the predators did hunt or scavenge sea otters, Stellar sea lions and harbor seals became the predominate food source for wolves.

The flexibility and resiliency of wolves becomes especially apparent in instances where wild ungulates and other wild prey are scarce or absent from the landscape.

Where wild prey is unavailable, one of the food sources that wolves turn to is domestic livestock, bringing them into direct conflict with humans. An increase in wolf predation on livestock has been tied to seasonal patterns such as the grazing season, when livestock are more vulnerable, with the wolves reverting to wild prey during the rest of the year.

Garbage represents another human-related food source for wolves. Scat analysis of wolves in Israel reveals that wolves consume not only meat scraps and fruit, but in the process also incidentally down non-food trash items such as human hair, plastic containers, cigarettes and eggshells. Dave Mech once found shards of broken glass in wolf scats. In Italy, prior to the restoration of large prey species, wolves often relied on town garbage dumps. In some instances, this scavenging behavior is seasonal, as in the case of a Minnesota wolf pack that foraged a municipal garbage dump during summer.

A more recent study from the Department of Environmental Sciences at the University of Tehran and the Forest Science and Technology Centre of Catalonia, Spain studied the diets of wolves in the Hamadan province of Western Iran, where livestock (sheep and goats) and agriculture are the main sources of income. It is also a region where medium-to-large wild prey are extremely scarce. Using GPS collars, researchers tracked and identified 312 wolf feeding sites, most of which were garbage dumps and poultry farms near villages. Of these, 142 kill sites and 170 other sites contained evidence of scavenging. Scat analysis showed that livestock comprised about 34% of wolves’ diet, garbage 23%, poultry 16% and European hare 15.4%.

Fruit is yet another food for wolves. Various studies of scat from the 1970s through the 1990s revealed fruit such as cherries, berries, apples, pears, figs, plums, grapes and melon in wolves’ diets across southern Europe (Italy, Greece, Spain and Portugal), Eastern Europe (Czech and Russia) and China. In 2020, biologists from Minnesota’s Voyageurs National Park and the University of Minnesota reported an adult wolf regurgitating wild blueberries for pups at a rendezvous site in the Greater Voyageurs Ecosystem.

What wolves eat has been one of the most studied aspects of wolf ecology. This is not surprising, as the wolf’s diet—be it wild or domestic ungulates—remains the main source of human-wolf conflict. Studies of what wolves eat reveal the influence on the wolf’s diet of factors such as the availability, size and vulnerability of prey, the terrain and climate, disease, fragmented landscapes and others. By providing a better understanding of wolves, their prey species and the ecosystems they inhabit, this research helps shape wildlife management policies while undoing myths and misperceptions about wolf predation.

Debra Mitts-Smith researches and writes about the wolf in literature and art. Her book, Picturing the Wolf in Children’s Literature, was published by Routledge in 2010. She is currently working on a cultural history of the wolf.

The International Wolf Center uses science-based education to teach and inspire the world about wolves, their ecology, and the wolf-human relationship.