More wolves don’t always mean more conflicts, as Peter David considers in Wisconsin. While early recolonizing wolves face challenges and may initially cause depredations, evidence from Wisconsin shows established populations can stabilize conflict levels. David highlights the importance of adaptation by wolves and humans, suggesting that coexistence is possible through understanding, non-lethal methods, and shared landscapes.

By Peter David

When wolves recolonize historic range—either through human intervention or natural range expansion—controversy seems to come with them. Often the first and strongest concern to arise revolves around depredations of livestock and, to a lesser degree, of hunting dogs or pets. Livestock depredations can be both costly and emotionally taxing to those who experience them, and state wolf recovery plans typically place great emphasis on developing and prescribing depredation responses. People unaccustomed to sharing the landscape with wolves also often feel threatened by their presence, despite the minimal threat wolves actually present. This spring, five northern California counties declared local states of emergency following dozens of livestock depredations by the state’s fledging wolf population, and concerns about public safety.

When wolves recolonize historic range—either through human intervention or natural range expansion—controversy seems to come with them. Often the first and strongest concern to arise revolves around depredations of livestock and, to a lesser degree, of hunting dogs or pets. Livestock depredations can be both costly and emotionally taxing to those who experience them, and state wolf recovery plans typically place great emphasis on developing and prescribing depredation responses. People unaccustomed to sharing the landscape with wolves also often feel threatened by their presence, despite the minimal threat wolves actually present. This spring, five northern California counties declared local states of emergency following dozens of livestock depredations by the state’s fledging wolf population, and concerns about public safety.

Wolves are relatively new on the scene in California. The first wolf known to venture into the state in nearly 90 years arrived in 2011, and it was only a decade ago that the first pack was confirmed. The population has slowly increased to an estimated 70 animals.

Since the population is expected to continue to increase, the natural concern in places like northern California is that more wolves will mean more depredations. It seems a reasonable assumption, and early in recovery periods, when wolves are colonizing a landscape new to them, this relationship often seems to hold true. But is it necessarily the case? Or might that relationship change as wolves become an established part of the local ecosystem?

Much like the early European colonists to North America who found starting a new life from scratch on an unfamiliar landscape more difficult than the generations that followed them, recolonizing wolves face more challenges than their descendants. Those descendants benefit from two fundamental qualities of wolves: they are intelligent, and they are highly social. Their ability to learn–and to pass that knowledge on to their young–is a unique and fundamental component of their ecology.

It suggests the possibility that over time wolves can learn and adjust to their new landscape, for example by determining the areas with the highest prey density or the most secure and suitable areas to den. After adults pass that knowledge on to their pups, subsequent generations may find survival somewhat easier. This in turn may reduce the grown pups’ likelihood of taking the risks associated with livestock depredations. Wolves that learn to avoid people and their livestock are likely to have higher survival rates and more progeny. Perhaps the behavior and impact of early wolf colonists is not indicative of what may follow, and perhaps the idea that more wolves mean more depredations deserves a closer look. A place one might look is Wisconsin.

Wisconsin was naturally recolonized circa 1974 by wolves that struck out from the Minnesota population, which was expanding under the protections of the Endangered Species Act. The animals in this front line did not find Wisconsin particularly welcoming; human-induced mortality was high, and two decades passed before the estimated wolf population in the state passed the modest mark of 50. However, at that point the population began a marked upward trajectory, following a fairly classic population growth curve. Over the next 11 years–by 2005– the population climbed to 435.

Wisconsin was naturally recolonized circa 1974 by wolves that struck out from the Minnesota population, which was expanding under the protections of the Endangered Species Act. The animals in this front line did not find Wisconsin particularly welcoming; human-induced mortality was high, and two decades passed before the estimated wolf population in the state passed the modest mark of 50. However, at that point the population began a marked upward trajectory, following a fairly classic population growth curve. Over the next 11 years–by 2005– the population climbed to 435.

Since an early population model suggested the biological carrying capacity for wolves in the state might be in the range of 500 animals, many people expected to see population growth start to slow. But it turns out the early model markedly underestimated carrying capacity. Either the model was not very good, or something had changed since it was developed. Two of the things that might have been most likely to change are related to behavior: wolves may have adapted their behavior to be more accepted by people, or people may have changed their thinking to be more tolerant of wolves. We will likely never know for certain, but likely both changes occurred to some degree.

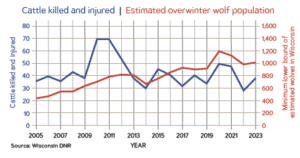

Over the last 20 years the Wisconsin wolf population has continued to grow. Recent estimates suggest the population may be plateauing (in the absence of hunting) at about 1100 animals, or about 2.5 times as many as in 2005. So have depredations also increased by about 2.5 times over these 20 years?

Data compiled by USDA Aphis Wildlife Services–the folks who track and respond to depredations in the state–indicates this was not the case. Their data shows that while the number of verified wolf complaints in the state can vary significantly from year to year (the highest level of verified complaints during this period was double that of the lowest), there has been no upward (or downward) trend in the number of verified depredation events over this period (Figure 1). Also, no upward trend has been seen in the number of farms with verified depredations, the number of cattle or pet dogs killed or injured, or the number of human health and safety incidents (Figures 2-5).

These data are consistent with the idea that as wolves move beyond the colonization period, they may be finding ways to co-exist more successfully with humans. In short, more wolves may not mean more depredations. This finding may be all the more surprising given that likely more wolves are using suboptimal habitat today than 20 years ago. (See Theresa Simpson’s article in the winter 2022 edition of International Wolf.)

One depredation metric has ticked upward in Wisconsin as the wolf population increased, though at less than half the rate of the population growth: the number of hunting dogs injured or killed (Figure 6). Why might this anomaly exist? One likely explanation may come from changes in human behavior.

One depredation metric has ticked upward in Wisconsin as the wolf population increased, though at less than half the rate of the population growth: the number of hunting dogs injured or killed (Figure 6). Why might this anomaly exist? One likely explanation may come from changes in human behavior.

Wisconsin has a significant tradition of hunting with hounds, including the hunting of black bears, whose population is currently about 23 times higher than the wolf population. As a result, the state has relatively liberal hunting, baiting and dog training regulations. While the increase in dog depredations could be related to the increase in the wolf population, it seems at least equally plausible that it is due to a change in the vulnerability of hunting dogs.

In 2016 the state eliminated its Class B bear license. This change made it possible for anyone to train dogs to hunt free-roaming wild bears statewide from July 1 through Aug. 31 without a license. Most dog depredations occur during the training period (rather than during the bear hunting season) when wolves are very protective of their pups. During this period of time, pups cannot defend themselves or easily escape when coming in contact with a pack of up to six hound dogs. Since no license is required, it is impossible to document the increase in training activity that resulted from this change. It is thought that because of its abundant bear population, large blocks of public land, and relatively cooler summer weather, Wisconsin became a popular destination for hounders from southern states to train their animals.

If the 20-year trend in dog depredations is divided into two 10-year periods, the more recent period—which aligns with the licensing change—shows a level of depredations that is about 50% higher than the previous 10-year period, but neither period displays an upward trend (Figure 7). Thus, the increase in hound depredations may not be due to more wolves, but more hound training taking place.

This data–and the idea that wolves may learn and adapt–may hold some other interesting implications. For example, it suggests that over time, non-lethal approaches to depredation reduction may yield benefits that lethal control may not provide. When a depredating wolf is killed, it may simply create a void for another unknowledgeable wolf to fill. However, if it is possible to successfully teach a wolf to avoid livestock, that void is not created, and that learning might be passed on. Unfortunately, the large and lengthy research effort necessary to support or contradict this idea is probably not politically possible.

The natural world tends to be complex, and often behaves in ways that are not straightforward. Likely the relationship between wolf population levels and livestock or pet depredation levels is influenced by many factors not explored in this article, including such things as prey abundance and vulnerability, habitat quality, weather impacts on prey species, animal husbandry practices, the impacts of lethal or non-lethal depredation control, the existence and design of wolf harvest seasons and more. But the Wisconsin experience clearly shows that more wolves do not necessarily mean more depredations. Given all the times and ways wolves have surprised us in the past, perhaps that should not come as a shock.

This article was originally published in the Fall 2025 edition of International Wolf magazine, which is published quarterly by the International Wolf Center. The magazine is mailed exclusively to members of the Center.

This article was originally published in the Fall 2025 edition of International Wolf magazine, which is published quarterly by the International Wolf Center. The magazine is mailed exclusively to members of the Center.

To learn more about membership, click here.

About the author: Peter David is a wildlife biologist who retired in 2022 from a career working for the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission, where his focus was primarily on the stewardship of wild rice, waterfowl and wolves. He serves on the board of directors of the International Wolf Center.

The International Wolf Center uses science-based education to teach and inspire the world about wolves, their ecology, and the wolf-human relationship.